Language is a powerful thing. The words we use say a lot about our beliefs and the world we live in. When it comes to gender politics, it is widely agreed that language should be as gender-neutral as possible to avoid implying that one gender (namely the male gender) is the norm. But the issue is far from straight-forward in German-speaking countries where a fierce debate is raging on the subject. Firstly, not everyone agrees that language should be changed in an artificial way for the sake of gender neutrality, and secondly, even if they do, there is no consensus on how it should be done.

by our guest author Sarah Hudson, our UK-based transcreator colleague with a passion for the German language

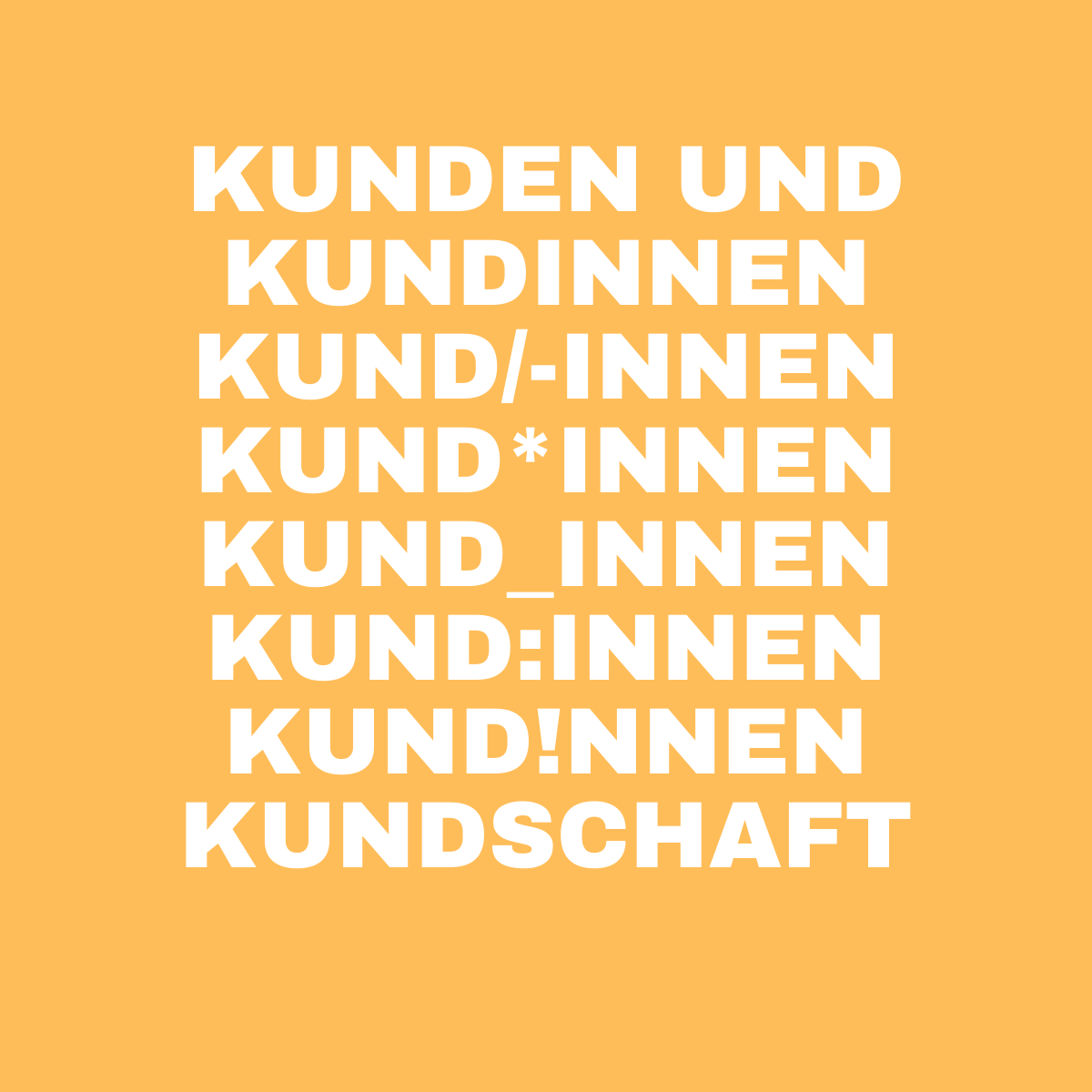

Strange stars and unusual underscores

The situation is quite complex in the German-speaking world because German is an inflected language. This means that, unlike in English, endings are placed at the end of certain nouns to denote gender, for example, Lehrer (male teacher), Lehrerin (female teacher). In recent years, a range of different options have been devised to make these kinds of nouns more gender-neutral. These range from using both the feminine and masculine forms of the noun (the paired form) to the more unusual ‘ich’ and generic neuter forms. So, for example, when German speakers want to write the word “Student”, they can in theory choose from a plethora of options:

Student und Studentin Paired form

Student/-innen Oblique

StudentInnen Connecting ‘I’

Student*innen Gender star (Gendersternchen)

Student_innen Gender gap

Student:innen Gender colon

Student!nnen Gender exclammation mark

Studierende Nominalised form

der Student Generic masculine

die Studentin Generic feminine

das Student Generic neuter

Studentich ‘Ich’ (I) form

Twinkle, twinkle, gender star!

The form chosen very much depends on the user’s preferences. The paired and oblique forms are most often found in official writing, for example, by the tax authorities; the connecting ‘I’ is the preferred option in Switzerland; and the city of Lübeck in northern Germany even decreed that everyone living in the area should use the colon because it is easy to find on a computer keyboard. Meanwhile, the gender star (Gendersternchen) has found favour in academic circles, partly because it covers non-binary forms. But despite its increasing popularity, not everyone likes it. In 2020, the Association for German Language (GfdS) called for it to be scrapped, along with other punctuation forms used for this purpose such as colons and underscores. The GfdS argues that they are not precise enough, and cause inconsistencies and grammatical confusion. And then there is the issue of how to pronounce words such as Student*innnen – Studentsterncheninnen is almost unpronounceable!

One gender marker for all

Despite these concerns, some German speakers and academics are calling for even more radical change to avoid discriminatory language of any kind. One option is the use of the generic neuter. This means that instead of saying ‘der Student’ (male student) or ‘die Studentin’ (female student), ‘das Student’ should be used. Another option advocated by German feminist linguist Luise Pusch is the use of the ‘ich’ suffix. ‘Ich’ is the German word for ‘I’. Luise Pusch is in favour of placing it at the end of nouns to create forms, such as ‘Studentich’. Some German speakers have also started to adopt a gender-neutral pronoun system using the word ‘xier’ to replace ‘he/she’. Graphic designer and linguist Anna Heger has even developed an entire alternative grammar system using these forms. For example, the sentence Sie packt ihren Koffer (she packs her suitcase) would become Xier packt xiesen Koffer and the same form would be used for ‘he packs his suitcase’. Similar systems are also being developed in French and Spanish, but it is very unlikely that any of these more radical approaches will be widely accepted any time soon. If nothing else, they are helping to stoke the fires of debate.

A triumph of reason

Various prominent newspapers, such as Die Welt am Sonntag in Germany and the Krone newspaper in Austria, have recently run surveys to gauge public opinion on the matter of gender-neutral German. The results of the surveys may possibly say more about the politics and age of the participants; however, they demonstrate that a high proportion of the general public is against the use of “artificial” non-gendered language, with Die Welt reporting that 63 per cent of those surveyed would rather the language was left well alone. Germany’s other prominent language association, Verein Deutsche Sprache, has described these results as a “triumph of reason” and believes that they underscore the fact that it is the media and academia that are trying to force change and not the average person in the street. There are also signs that some people are becoming more than impatient about recent attempts by organisations to impose gender-sensitive language. An Audi employee has recently filed a lawsuit against the company because he believes its “dictatorially prescribed” language infringes his personal rights.

Case not closed

It is therefore clear that many people in German-speaking countries are not in favour of their language been radically changed, but this does not mean that the matter of gender-friendly language is closed. Many organisations, including government departments, are still laying out clear policies to increase the visibility and rights of women, transgender and non-cis people, and this extends to the use of language. It could be argued that the debate around the subject in German-speaking countries is diverting attention away from the real issue at hand, in other words, the rights of marginalised groups. Moreover, focusing on concerns about controlling or policing language ignores the fact that providing different options actually gives people the opportunity to decide for themselves and represents the exact opposite of control. The issue therefore centres on choice. When all is said and done, the debate is at least helping to stimulate discussion and raise awareness about an important subject.

Navigating the gender-friendly German minefield

So, what should you do when you need to translate information or marketing materials into German? The simple answer: know your audience and ask them what they would prefer. Their preferences may depend on their own personal stance or on the rules the organisations they represent follow. It is especially important to work with native German-speaking translators or transcreators who are knowledgeable about the different issues and who can provide you with the best possible advice. Experienced translators keep up to date with prevailing opinions and understand how to comply with the wishes and expectations of your target audience. A trusted language specialist can also help you compose a style guide to ensure the rules are followed consistently across your organisation to avoid any unnecessary uncertainty or confusion. It is also important to be very careful if you use machine translation tools such as Google Translate or DeepL because they do not handle non-gendered language accurately or consistently. If you do decide to use machine translation for simple and repetitive texts, it is definitely worth working with a trained linguist who can check that the machine output is correct and appropriate because getting it wrong can cause significant reputational damage.

Language is not set in amber and is constantly evolving to reflect our changing lives, experiences and cultures. Some of the seemingly madcap options mentioned above may actually become mainstream one day. In the meantime, we should think of Bob Dylan’s sage words, “The times they are a-changin’” – to remind us that we must do our best to change with them too.